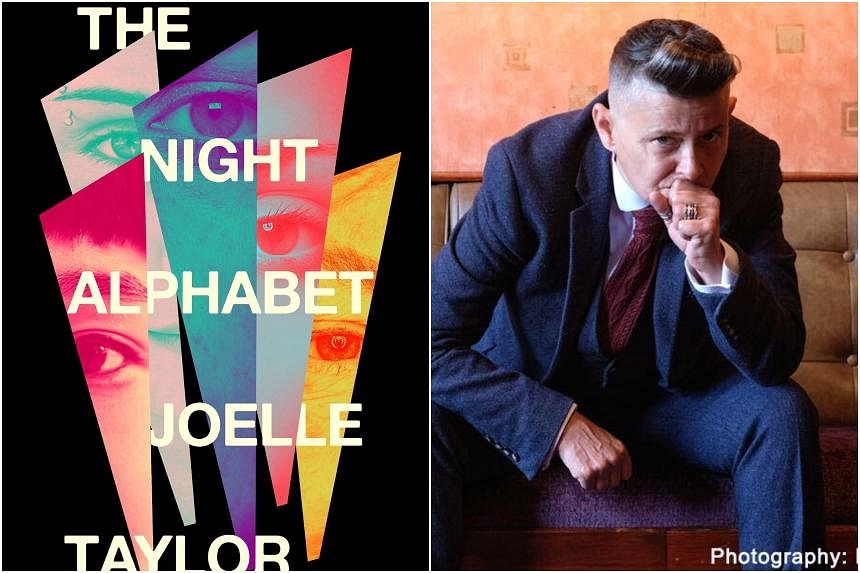

The Night Alphabet

By Joelle Taylor

Fiction/Riverrun/Paperback/432 pages/$32.95/Books Kinokuniya

4 stars

T.S. Eliot Poetry Prize-winning writer Joelle Taylor brings her poetic sensitivity to prose in this ambitious debut novel, a phantasmagoric series of linked stories that weaves a history of women in surreal and gritty detail.

The Night Alphabet has some affinity with her award-winning fourth collection of poems, C+nto & Othered Poems (2021), which explores the private lives of women from the butch counterculture. She blew audiences away in a reading of this searing poem performed at the Singapore Writers Festival in 2022.

Set in Hackney in 2233 in a world where “even the skin is gentrified” and digital tattoos are the norm, a tattoo-covered Jones walks into a retro tattoo parlour with a strange request – and it is not just because she asks for a final inking with a rotary needle rather than laser.

Jones wants her mother’s blood mixed into ink and transformed into a tattoo that will span her entire body, linking all her existing ones together. Her brief baffles the two artists Cass and Small, who begin to listen intently – with disbelief – as their client effectively time-travels in their presence with her stories.

These episodes are what Jones refers to as “rememberings”, a phenomenon which links her to generations of women in her family, even those she has not met.

Every tattoo on her body is a unique trap door which takes her into places such as the coal mines of 19th-century Lancashire, a lesbian bar known as the Maryville and the mind of an involuntary celibate (also known as “incel”) murderer.

Taylor, who is a queer and working-class author, has written a poet’s novel which revels in the capaciousness of metaphors and displays an affection for non-sequitur’s suggestive powers. Her sentences often demonstrate a lyrical allure: “My mother leaked tattoos. They materialised across her body, black ink to tissue paper, a slowly spreading water colour.”

While not a conventionally structured novel, the story-within-a-story narrative is reminiscent of older forms of oral storytelling such as 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron – where 10 young people take turns to tell stories as they escape the Black Death in Florence – or the One Thousand And One Nights, where Scheherazade tells stories to save her life.

Taylor’s novel, similarly, is concerned with the life-saving power of stories in a time of extreme violence against women. Her characters – vigilante sex workers, victims of murder, vulnerable women exploited by sex traffickers, young girls who work under dangerous conditions, and queer women – often face death.

Many of these are incendiary stories of injustice. A tale of a young girl who disguises herself as a boy to work in the mines after her father’s death, for example, reveals gender inequalities around work conditions and is also a study on gender performance, to use an anachronistic word, in the 19th century.

After a particularly harrowing story, Jones says of the tattoo artist: “Small will say she is angry at the traffickers, about what they did and continue to do to these discarded girls. But the truth is that she is angry at me for telling the story, for setting it free in the world.”

She continues: “You cannot take away an idea once it is freely given, you cannot unthink. We are always angry at the person telling the story, which shows just how real fiction can be.”

Like the two tattoo artists, the reader might also harbour a deep cynicism and suspicion about these loose vignettes at the start of The Night Alphabet. But, gradually, Taylor’s stories throw up a range of emotions: anger, solace and even the possibility of hope against the odds.

If you like this, read: Kang Hwagil’s Another Person, translated by Clare Richards (Pushkin Press, 2023, $23.33, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/45nsxoh). The tightly plotted thriller by a young South Korean feminist is structurally quite different from The Night Alphabet and is set in another cultural context, but both books speak to the contemporary moment where the topic of violence against women is gaining more attention in the literary world.